In contemporary Australia, Aboriginal Land Councils such as the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC) and the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) are increasingly targeted by coordinated settler-colonial resistance masquerading as environmental advocacy, heritage protection, and community concern.

This resistance, often led by non-Aboriginal individuals and groups with no legitimate cultural authority, functions to delegitimise lawful Aboriginal governance and disrupt truth-telling processes.

Through an in-depth examination of the Patyegarang (Lizard Rock) development and the manufactured controversy over the so-called Kincumber Wetlands, this article explores how settler environmentalists, false Aboriginal claimants, conspiracist ideologues, and complicit media actors converge to undermine Aboriginal land rights. It argues that such opposition is not merely local dissent but a systemic backlash against Aboriginal sovereignty that threatens the social and legal fabric of the nation.

False Custodianship and Cultural Appropriation

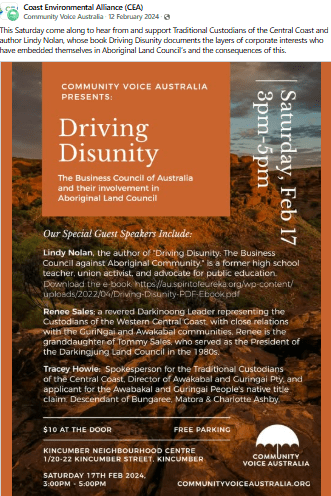

A key strategy in settler resistance is the invention and deployment of false custodianship. The self-styled “GuriNgai” group exemplifies this trend. Comprised of non-Aboriginal individuals including Neil Evers, Amanda Jane Reynolds, Dennis Jones, and Tracey Howie, the group claims cultural authority over the Northern Beaches, Hornsby, and Central Coast regions.

However, the term “GuriNgai”—widely used by this group—is a colonial fabrication with no historical legitimacy in the Sydney region. Scholarly research and community testimony confirm that the true Guringay (Gringai) people originate north of the Hunter River, in the Dungog and Gloucester regions (Aboriginal Heritage Office, 2015; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024; McEntyre, 2024).

The appropriation of the Guringai name and associated cultural symbols has had profound consequences. It distorts public understanding of Aboriginal history, marginalises legitimate community voices, and displaces lawful custodianship with fabricated identities.

The MLALC’s 2020 letter to the NSW Premier denounced these false claimants, reaffirming that no Guringai people exist in their region. Yet these false identities continue to be legitimised by local councils, media, and public events, including opposition to lawful Aboriginal developments such as the Patyegarang proposal.

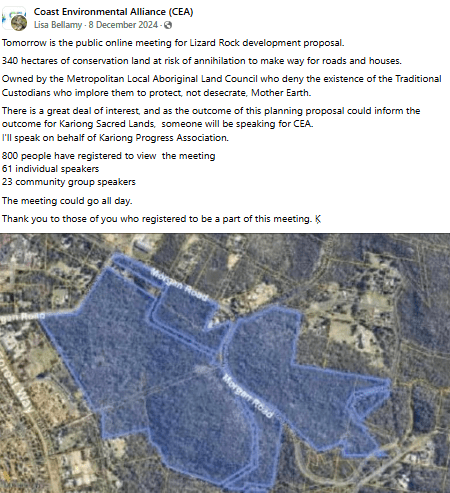

The Patyegarang Proposal and Organised Opposition

The MLALC’s proposal to develop part of its land at Lizard Rock (Patyegarang) was met with fierce opposition from self-appointed cultural figures and environmental activists who falsely claimed to speak on behalf of traditional custodians. Despite the legitimacy of MLALC under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), opponents—backed by settler networks and environmentalist groups—framed the proposal as destructive to heritage and nature. These critiques, however, ignored MLALC’s statutory obligations and its own community-driven cultural protocols.

This form of resistance reflects a broader settler-colonial tactic: casting Aboriginal organisations as “developers” while positioning white-led opposition as defenders of “Country.” As Moreton-Robinson (2015) argues, such strategies enact the logic of white possessiveness, where settlers reserve the right to determine what is authentically Aboriginal and who has the right to speak for Country.

Manufacturing Outrage: The Kincumber Wetlands Case

The case of the so-called Kincumber Wetlands controversy demonstrates the tactical use of misinformation in delegitimising Aboriginal land rights. In late 2023, Jake Cassar and Seamus Turton circulated unfounded rumours that a Woolworths was to be built on wetlands in Kincumber.

These claims were not only inaccurate—there was no development application or lease—but were clearly aimed at inflaming public sentiment against DLALC. Councillor Jared Wright confirmed the absence of any such plans, while Cassie Roese (2025) noted that the land was undergoing preliminary review consistent with DLALC’s lawful rights.

Turton’s public denial that the land was “Darkinjung Country,” along with his misleading statistics about community representation, echoed earlier attacks on Aboriginal authority at Kariong and Belrose (Cooke, 2025a, 2025b). These tactics recycle colonial tropes of Aboriginal incapacity while elevating non-Aboriginal figures like the GuriNgai as “true custodians,” in direct contradiction of genealogical evidence and community recognition.

Settler Conspirituality and Identity Fraud

These coordinated efforts to undermine Aboriginal authority are not confined to cultural misrecognition—they are also part of a wider ideological movement. As Carlson and Day (2023) argue, “settler conspirituality” enables white activists to merge New Age spiritualism, anti-government sentiment, and far-right conspiracism. Cooke (2024a, 2024b) connects these beliefs to sovereign citizen ideologies, ecofascism, and the weaponisation of post-truth discourse.

By donning Aboriginal symbols, staging pseudo-ceremonies, and invoking spiritual “connections to Country,” false custodians displace legitimate voices and enact a form of symbolic violence. These activities dilute public understanding of Indigenous sovereignty and discredit Aboriginal-led institutions.

Broader Impacts: Undermining Aboriginal Organisations and Public Trust

The broader social impact of these campaigns is profound. Aboriginal Land Councils are not simply land managers; they are expressions of Aboriginal self-determination and cultural continuity. When their authority is undermined—by settler activists, false claimants, or complicit media—the result is weakened governance, policy confusion, and public mistrust.

The NSW Aboriginal Land Council and NTSCORP (2011) emphasised that Aboriginal organisations are routinely excluded from heritage reform processes, treated tokenistically, or bypassed altogether. Similarly, the NSW Council for Civil Liberties (2021) warned that Aboriginal heritage is still treated under legal frameworks as environmental property rather than a living, sovereign system of law and cultural practice.

By enabling or ignoring identity fraud, institutions risk legitimising colonial revisionism and failing to meet obligations under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). False custodianship is not a cultural misunderstanding—it is a legal, political, and moral failure.

Conclusion: Truth-Telling, Recognition, and Cultural Integrity

The campaigns against MLALC and DLALC are not isolated incidents; they are expressions of a deeper colonial impulse to control Aboriginal identity and limit Indigenous sovereignty. The adoption of Aboriginal motifs by non-Aboriginal individuals, the spreading of false historical narratives, and the opposition to legitimate land councils all serve a common purpose: maintaining settler control.

To move forward, Australian institutions must embrace a rights-based framework grounded in cultural integrity, genealogical continuity, and genuine community recognition. Unverified self-identification, no matter how well-intentioned, cannot replace community-validated identity. Truth-telling is not a symbolic gesture but a necessary practice to restore justice and ensure the survival of Aboriginal cultural authority.

Affirming Aboriginal sovereignty demands not only resisting settler lies but actively dismantling the platforms that enable them. In doing so, we create a society where all Australians—Indigenous and non-Indigenous—can contribute to a future rooted in respect, truth, and lawful recognition.

JD Cooke

References

Aboriginal Heritage Office. (2015). Filling a void: A review of the historical context for the use of the word “Guringai”. https://www.aboriginalheritage.org

AIATSIS. (2022). Native Title in Australia: Understanding the Legislation. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Bosler, N. (2010). The Story of Bob Waterer and his Family 1803–2010. Aboriginal Support Group–Manly Warringah Pittwater.

Carlson, B., & Day, M. (2023). So-called sovereign settlers: Settler conspirituality and nativism in the Australian anti-vax movement. Humanities, 12(5), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050112

Cooke, J. D. (2024a). Indigenist research, cultural theft, and the weaponisation of identity by non-Indigenous actors. Unpublished manuscript.

Cooke, J. D. (2024b). Settler conspirituality, post-truth politics, and the crisis of Aboriginal identity in contemporary Australia. Unpublished manuscript.

Cooke, J. D. (2025a). Indigenous identity fraud and conspirituality on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, Hornsby Shire and Central Coast. Guringai.org. https://guringai.org/2025/06/06

Cooke, J. D. (2025b). The false mirror: Settler environmentalism, identity fraud and the undermining of Aboriginal sovereignty on the Central Coast. Guringai.org. https://guringai.org/2025/06/07

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2021). Aboriginal Cultural Authority on the Central Coast of New South Wales. Wyong, NSW.

Fraser, J. (1892). The aborigines of New South Wales. Charles Potter, Government Printer.

Lissarrague, A., & Syron, R. (2024). Guringaygupa Djuyal, Barray: Language and Country of the Guringay people. https://hunterlivinghistories.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Guringaygupa-djuyal-barray05-11-2024.pdf

McEntyre, E. (2024). John Jonas – Guringai. Personal research archives.

Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2020, June 3). Letter to NSW Premier Re: Guringai Claimants [PDF].

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

NSW Aboriginal Land Council & NTSCORP. (2011). Submission in response to the reform of Aboriginal culture and heritage in NSW. https://www.alc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/29NSWALCNTSCOR.pdf

NSW Council for Civil Liberties. (2021). Submission to the NSW Legislative Council Standing Committee on Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Bill 2022. https://www.nswccl.org.au/aboriginal_cultural_heritage_submission

Premier NSW. (2020). Final Draft MLALC Letter Re Guringai Claimants, 3rd June 2020. Sydney, NSW.

Roese, C. (2025, February 24). [Comment on Kincumber land controversy]. Facebook.com.

Turton, S. (2025, February 19). [Post in Save Kincumber Wetlands Facebook group]. Facebook.com.

Whitfield, W. (2001). Oral History Interview by Rosemary Block, 7 Sep 2001. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Wright, J. (2025, February 21). [Statement on Carrak Road Reserve, Kincumber]. Central Coast Council.

Wyong Coal. (2015). Wyong Coal sign mutual agreement with Guringai Tribal Link Aboriginal Corporation. Internal corporate report.

Leave a comment