The speech titled A Scar on Country, delivered under the name “Walkaloa Wunyunah” at a Central Coast Council meeting, is presented as a spiritually grounded and culturally legitimate opposition to proposed development at Winney Bay, New South Wales. Its tone and language attempt to situate the speaker as a Traditional Custodian of so-called “Guringai Country,” articulating a narrative of Aboriginal law, kinship, and belonging. However, a comprehensive critical appraisal reveals that the speech is not a product of Aboriginal cultural authority but rather a performance authored by a non-Aboriginal individual, Tracey Howie, whose long record of identity appropriation and misrepresentation is well documented (Cooke, 2025a; 2025b).

Howie, who also uses the alias Walkaloa Wunyunah, has repeatedly claimed direct matrilineal descent from Bungaree and Matora of Broken Bay—ancestral figures of great importance in early colonial Aboriginal history. Yet these claims have been unequivocally refuted through genealogical records, oral histories, anthropological analysis, and Aboriginal community rejection. The true descendants of Bungaree and Matora have established an unbroken lineage documented by birth, marriage, and death records and oral tradition (Cooke, 2025a). These descendants have never identified with the label “Guringai,” nor have they authorised its use as a representation of their ancestral identity.

The term “Guringai” itself is a colonial invention, introduced by Scottish ethnologist John Fraser in 1892 as a speculative, unverified attempt to consolidate disparate language groups into an imagined cultural bloc (Fraser, 1892). Fraser’s assertions have been rejected by linguists, Aboriginal knowledge holders, and cultural institutions (Aboriginal Heritage Office [AHO], 2015; Syron & Lissarrague, 2024). As confirmed in Guringaygupa Djuyal Barray (Syron & Lissarrague, 2024), the true Guringay people are based north of the Hunter River and have no connection to Sydney or the Central Coast. Despite this, the invented “Guringai” label has been revived by individuals such as Howie and her associates—notably Warren Whitfield—to manufacture Aboriginal identity and claim cultural authority where none exists (Cooke, 2025b).

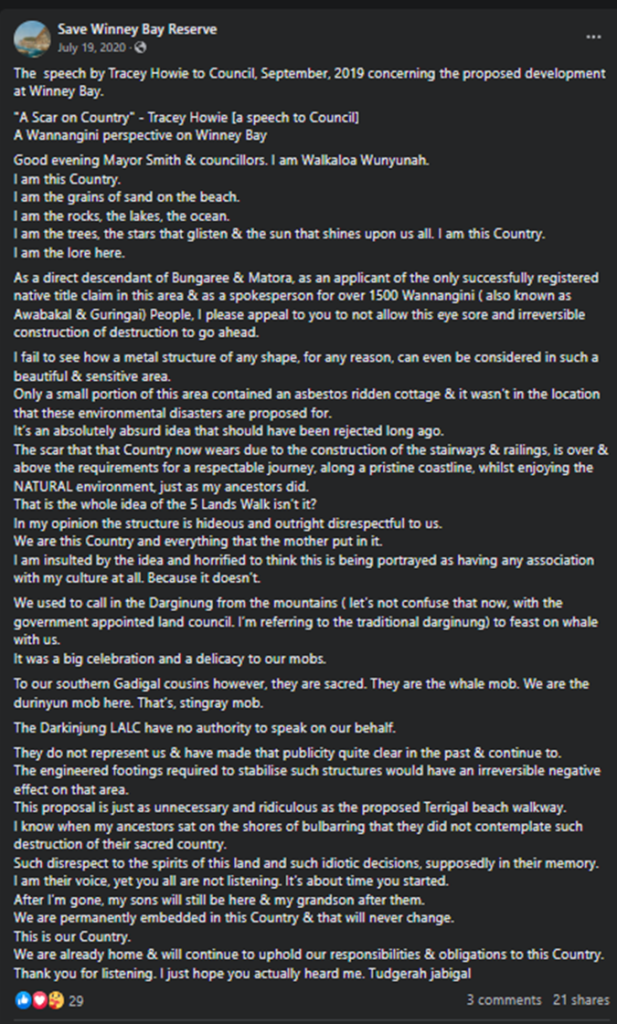

The speech itself is laden with poetic and metaphorical language. Phrases such as “I am the grains of sand… I am the lore here” are deployed to evoke a romanticised Aboriginal spirituality, yet these statements are devoid of anchoring in genuine cultural practice, ceremonial law, or community-validated kinship obligations. Instead, they reflect a settler-colonial appropriation of Aboriginal idioms, repackaged to simulate belonging and spiritual authority. Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) has critiqued such tactics as examples of the “white possessive,” whereby land and identity are claimed through discourses of empathy and connection while erasing the actual sovereign presence of Indigenous Peoples.

More concerningly, Howie claims in her speech to represent over 1,500 “Wannangini (also known as Awabakal and Guringai) people” and to be a registered Native Title applicant. This assertion is demonstrably false. The term “Wannangini” has no known linguistic, ethnographic, or ceremonial basis and appears to be an invention by members of the fraudulent GuriNgai Aboriginal Corporation to mimic the naming conventions of real Aboriginal clans. The native title application NC2013/002, which Howie co-authored, was discontinued after failing to meet the requirements for registration, and no determination of Aboriginality or traditional ownership was made in their favour (Kwok, 2015; DLALC, 2022).

The rejection of these claims by established Aboriginal Land Councils is comprehensive. The Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC), along with the Darkinjung, Awabakal, Worimi, Biraban and Mindaribba Land Councils, issued a formal letter to the NSW Premier in 2020 stating that none of the Guringai claimants are recognised by community or hold legitimate descent from the claimed ancestors (MLALC et al., 2020). This statement aligns with anthropological reports and the independent findings of the Registrar under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), which further discredits the cultural standing of the so-called GuriNgai movement (Courtman, 2020).

The speech also takes aim at the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC), asserting that it lacks authority to speak for Country. This is not only false but also reflects a broader settler tactic of undermining Aboriginal-controlled institutions. DLALC, like all LALCs under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983, is a democratically governed statutory body tasked with managing lands, heritage, and cultural affairs in accordance with the collective will of its Aboriginal members. Howie’s attempt to bypass this governance structure in favour of a self-declared and unaccountable alternative constitutes a direct assault on Indigenous self-determination and lawful authority (NSWALC, 2019).

The use of the alias “Walkaloa Wunyunah” is itself a strategic act of disguise. Howie has cycled through various titles, including “Guringai Elder,” “Wannangini custodian,” and “Durinyun spokeswoman,” each constructed to simulate deep cultural connection and specificity. Yet these identifiers are without linguistic, historical, or ceremonial foundation. The term “Durinyun,” purportedly meaning “stingray mob,” does not correspond with any recognised Aboriginal naming system for clans or skin groups in the Sydney Basin or Central Coast. As such, it must be regarded as an invented construct, part of a broader settler performance of Indigeneity.

Howie’s environmental appeals within the speech—framing the Winney Bay structure as an “eyesore” and a “scar on Country”—are emblematic of what Cooke (2025b) terms “eco-Indigeneity fraud.” This phenomenon describes how non-Aboriginal activists adopt Aboriginal identities and narratives in environmental disputes to assert moral authority while advancing settler interests. This tactic has been especially prevalent in opposition to land development projects led by Aboriginal Land Councils. Groups such as the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), with whom Howie has closely aligned, have repeatedly opposed Aboriginal-led development at Kariong, Kincumber, and Lizard Rock by invoking false custodianship and settler-environmentalist rhetoric (Cassar, 2023; Cooke, 2025b).

The closing declaration in Howie’s speech—”We are already home and will continue to uphold our responsibilities and obligations to this Country”—is deeply misleading. While on the surface it gestures to Aboriginal sovereignty, in practice it serves to erase the true sovereign custodians and assert illegitimate control over Country. It reflects what Carlson and Day (2023) identify as settler conspirituality: a blend of spiritualised settler logic, identity appropriation, and anti-institutionalism that undermines Aboriginal collective governance.

In conclusion, A Scar on Country is not an authentic cultural statement. It is a staged performance of Indigeneity authored by Tracey Howie, a non-Aboriginal individual who has employed fabricated genealogies, invented tribal names, and settler-environmentalist alliances to insert herself into Aboriginal political and cultural spaces. Her assertions of descent from Bungaree and Matora are demonstrably false. Her rejection of DLALC authority and use of terms like “Guringai,” “Wannangini,” and “Durinyun” represent a deliberate campaign of disinformation. As such, this speech—and the wider GuriNgai movement it exemplifies—should be understood as a form of cultural appropriation, identity fraud, and settler colonial interference in Aboriginal sovereignty.

JD Cooke

References

Aboriginal Heritage Office. (2015). Filling a void: A review of the historical context for the use of the word ‘Guringai’. https://www.aboriginalheritage.org

Brook, J., & Kohen, J. (1991). The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A history. UNSW Press.

Carlson, B. (2016). The politics of identity: Who counts as Aboriginal today? Aboriginal Studies Press.

Carlson, B., & Day, M. (2023). So-called sovereign settlers: Settler conspirituality and nativism in the Australian anti-vax movement. Humanities, 12(5), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050112

Cassar, J. (2023). Coast Environmental Alliance: About Us. https://www.coastenvironmentalalliance.com.au/

Cooke, J. D. (2025a). Tracey Howie and family: False claims to Bungaree ancestry. https://guringai.org/2025/01/07/tracey-howie-and-family/

Cooke, J. D. (2025b). White possession, settler conspirituality, and the Guringai cult: Indigenous identity fraud as neocolonial violence in contemporary Australia. https://guringai.org/2025/05/21/white-possession-settler-conspirituality-and-the-guringai-cult-indigenous-identity-fraud-as-neocolonial-violence-in-contemporary-australia/

Courtman, N. (2020, August 21). Letter to the President of the National Native Title Tribunal re ILUA with the St Ives Pistol Club.

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2022). Submission to the Central Coast Council First Nations Accord. https://dlalc.org.au

Fraser, J. (1892). An Australian language as spoken by the Awabakal. Government Printer.

Kowal, E., & Watt, E. (2023). Indigenous identity fraud in the neoliberal settler state. In E. Kowal & B. Carlson (Eds.), Indigenous identity fraud in settler states (pp. 45–70). Routledge.

Kwok, N. (2015). Anthropological connection report: Awabakal and Guringai People NC2013/002.

Leroux, D. (2019). Distorted descent: White claims to Indigenous identity. University of Manitoba Press.

Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council, Darkinjung LALC, Awabakal LALC, Mindaribba LALC, Worimi LALC, Biraban LALC. (2020, June 3). Joint Letter to Premier Berejiklian regarding Guringai claimants. [Unpublished].

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press. National Library of Australia. (2009).

Interview with Tracey-Lee Howie by Rob Willis. Rob and Olya Willis folklore collection. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4735539 NSW

Syron, R., & Lissarrague, A. (2024). Guringaygupa djuyal barray: The true story of Guringay country, language, and identity.

Leave a comment