Abstract

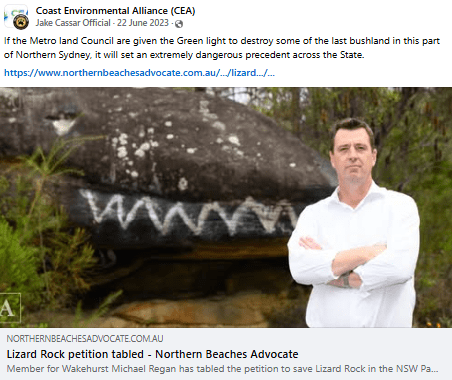

This article interrogates the digital activism of the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), a Central Coast environmental protest network led by Jake Cassar.

Drawing upon qualitative content analysis of 207 Facebook posts published between January 2023 and June 2025, it critically examines CEA’s strategic deployment of cultural appropriation, conspiratorial populism, and false Aboriginal identity claims to delegitimise Aboriginal land rights.

By contextualising CEA within broader frameworks of settler colonialism, sovereign citizen ideology, and New Age environmentalism, this study reveals how settler cults function as vehicles of digital dispossession.

The analysis demonstrates that CEA’s campaigns target Aboriginal-led developments with a consistency and ideological precision that cannot be explained by ecological concern alone. Instead, CEA constitutes a settler-spiritual movement that re-inscribes colonial dominance through pseudo-Indigenous performance, cultural mimicry, and digital propaganda.

1. Introduction: Environmentalism or Settler Spiritualism?

Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), established by Jake Cassar, self-identifies as a grassroots environmental organisation concerned with preserving natural landscapes and protecting sacred Aboriginal sites.

Yet a close analysis of its online presence reveals an ideological apparatus aimed not at environmental conservation, but at undermining Aboriginal sovereignty.

Between 2023 and 2025, CEA orchestrated numerous digital campaigns targeting Aboriginal-led development projects including Kariong, Kincumber, the 5- Lands Walk, and Lizard Rock.

These projects were all pursued by recognised Aboriginal people, organisations, and landholding bodies, most prominently the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) and the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (Metro LALC), under the authority of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW).

CEA’s rhetoric relies on aestheticised spirituality, emotional imagery, and appeals to false Aboriginal authority figures.

Their digital campaigns frame DLALC and Metro LALC as threats to Country while amplifying voices from a network of known false Aboriginal identity claimants, many of whom are associated with the so-called GuriNgai group.

Rather than operating as an ecological movement, CEA deploys a form of what Day and Carlson (2023) describe as “settler conspirituality”, a synthesis of New Age mysticism, conspiracy rhetoric, and anti-government ideology masquerading as cultural solidarity.

This emergent political spirituality often involves racialised imaginaries, settler grief, and esoteric mythologies of place which supplant Indigenous authority with settler intuitions of sacredness.

CEA thus becomes not only a campaign network but a stage for what Deloria (1998) terms the “performance of Indianness,” wherein white Australians construct imagined kinship with Aboriginal land, heritage, and identity while undermining the political legitimacy of actual Aboriginal voices.

This performance is neither incidental nor harmless. It reproduces the structures of settler colonialism in digital form, transforming social media platforms into theatres of spiritual possession, narrative inversion, and epistemic violence.

2. Methodology: Analysing the Digital Footprint

This study employed qualitative content analysis to examine the public Facebook activity of the Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) and its affiliated campaign pages between January 2023 and June 2025.

A dataset of over 200 posts was collated, including original posts, event pages, comment threads, reposted media, and protest flyers.

The sample was purposive rather than random, focusing specifically on content related to Aboriginal land, custodianship, and development controversies.

The goal was to identify recurring narratives, rhetorical patterns, visual aesthetics, and user engagement behaviours that aligned with conspiratorial, pseudo-Indigenous, or anti-Aboriginal sentiments.

To establish interpretive validity, each post was coded according to thematic categories informed by existing literature on settler colonialism, digital activism, and conspiracy discourse.

These categories included spiritualised environmentalism, attacks on Aboriginal governance, sovereign citizen rhetoric, use of New Age terminology, and signs of cultic language or behaviour.

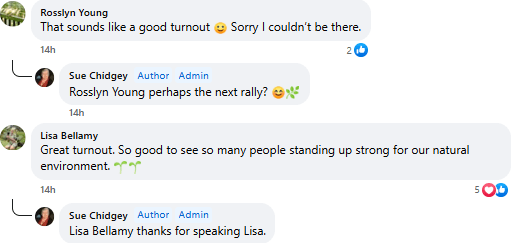

Authorship patterns were also tracked across multiple campaigns to identify key influencers, such as Jake Cassar, Lisa Bellamy, Emma French, and Kate Mason, whose contributions consistently shaped the tone, narrative arc, and visual branding of the movement.

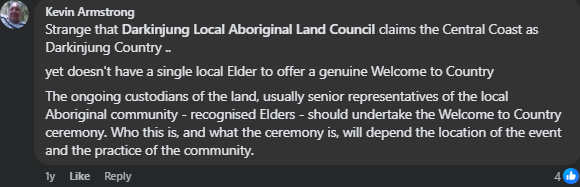

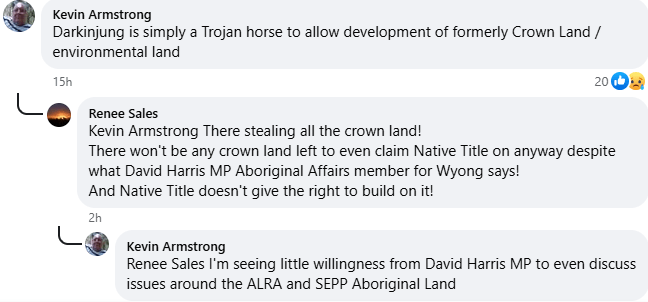

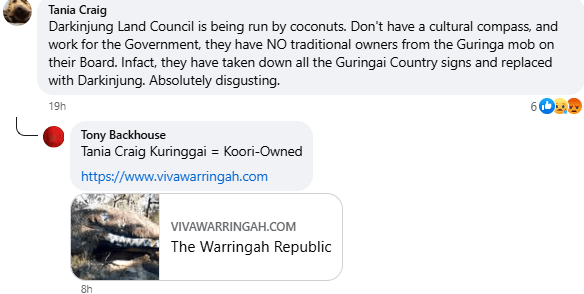

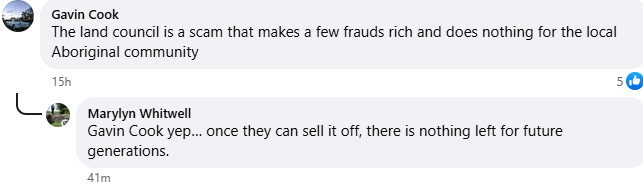

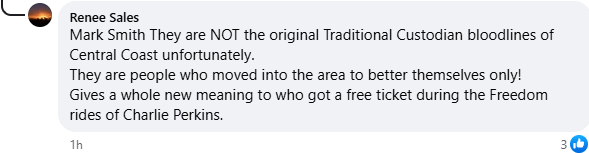

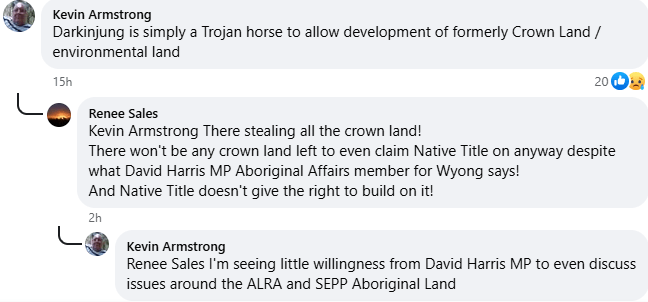

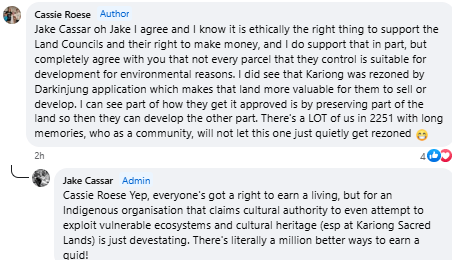

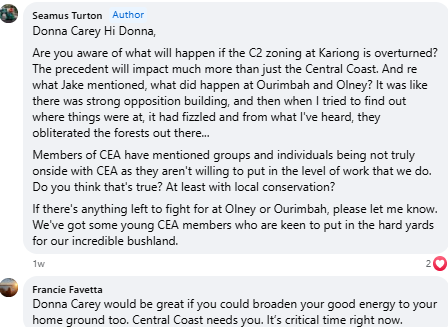

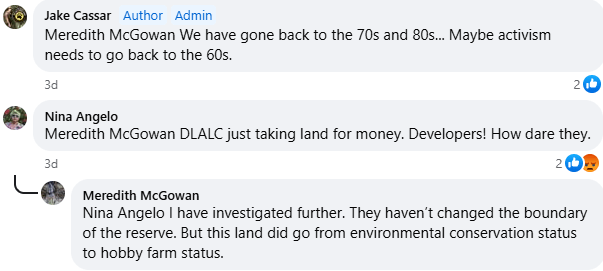

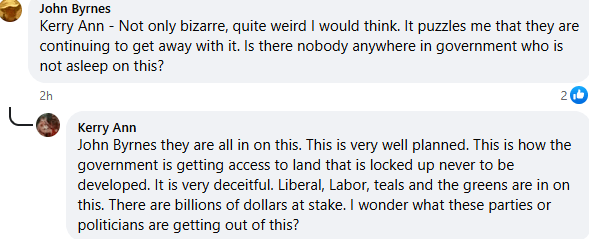

While the analysis remained focused on textual and visual media, particular attention was paid to comment thread dynamics, where follower interactions often revealed underlying ideological commitments.

Threads were assessed for the presence of conspiracist thinking, expressions of anti-government sentiment, distrust of Aboriginal organisations, and claims of secret or esoteric knowledge, features consistent with the “conspirituality” typology identified by Ward and Voas (2011) and further developed in the Australian context by Day and Carlson (2023).

Although the study does not claim quantitative generalisability, it does provide a detailed snapshot of CEA’s evolving discursive landscape.

The triangulation of digital content, public records, and media reporting supports a rigorous qualitative interpretation of how settler-conspiritual narratives are constructed, disseminated, and normalised in CEA’s online presence.

Furthermore, the analysis is contextualised within a growing body of literature on digital settler colonialism, Indigenous identity fraud, and the cultural politics of environmental protest.

3. Strategic Campaigning and the Digital Cultivation of Settler Conspirituality

The Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) is more than an environmental protest group; it is a calculated communications network designed to manufacture legitimacy through aesthetic affect, myth-making, and algorithmic engagement.

Over time, it has refined a strategic campaign model marked by repetition, spectacle, and cultural substitution.

At the centre of this strategy is the careful deployment of emotionally charged imagery, pseudo-sacred language, and protest theatre that fuses ecological concern with spiritual narrative.

This hybrid rhetoric operates in a post-truth environment where appeals to authenticity and “feeling” frequently override the demands of evidence, law, or Aboriginal authority (Kolopenuk, 2023; Moreton-Robinson, 2015).

This strategy is not incidental. CEA’s coordinated use of livestream events, t-shirt slogans, heritage mythologies, and algorithmically boosted content reveals a high degree of narrative planning.

For instance, the repeated invocation of “Kariong Sacred Lands” as a spiritually significant site, despite its formal recognition as Darkinjung LALC land under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), reflects a deliberate attempt to reframe public understanding of custodianship.

As with the Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign, the invocation of a sacred imperative operates as a spiritual alibi for opposing Aboriginal land management (Cooke, 2025a; Ingram, 2008).

This is a clear expression of what Bhabha (1994) identifies as settler mimicry, a performance that copies the form of Aboriginal cultural authority while hollowing out its substance.

Moreover, the consistency across campaigns, Kariong, Bambara, Lizard Rock, and Kincumber, reveals a thematic template.

This includes the romanticisation of nature, the demonisation of development, the platforming of pretendians (false Aboriginal claimants), and the ritualised mobilisation of settler guilt into performative allyship.

CEA’s messages often merge ecological preservation with mystical language about star-beings, Dreaming portals, and ancient energy fields, thus aligning with a conspiratorial tradition of spiritualised white faux-environmentalism (Carlson & Day, 2023).

In this model, Aboriginal people are either replaced or selectively represented through false claimants who reinforce the mythos.

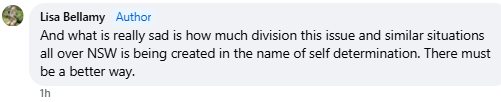

Key actors including Jake Cassar, Lisa Bellamy, Colleen Fuller, Emma French, and Nina Angelo, recur across campaigns, not only as organisers but as symbolic figures of moral righteousness.

Cassar’s public identity as a bush tracker, wildlife protector, and Yowie hunter is repeatedly staged as a credential for environmental insight.

This is not merely personal branding; it is part of a broader charisma-driven mobilisation strategy typical of cultic movements (Whitsett & Kent, 2003).

As Crabtree et al. (2020) argue, charisma in settler-colonial contexts often functions as a substitution for Culture, expertise, and authority, granting white leaders a spiritually charged mandate to intervene in cultural debates to which they have no legitimate connection.

The strategic nature of CEA’s campaigns also reveals a high level of digital sophistication.

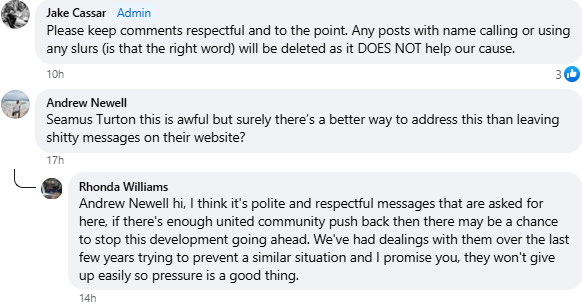

Posts are timed around peak user activity, hashtags are used to drive cross-platform engagement, and comment moderation is exercised to create the appearance of consensus.

The suppression of dissenting voices, particularly Aboriginal critiques, reflects a controlled digital environment in which epistemic authority is manufactured and maintained.

This digital control mirrors offline tactics such as monopolising media access, staging press events without counter-narratives, and placing fraudulent claimants at the centre of cultural consultation.

In sum, CEA’s campaign model is strategic in both method and message.

It combines affective storytelling, digital choreography, and settler mimicry into a potent instrument of narrative displacement.

By aestheticising land defence while erasing legitimate Aboriginal custodianship, CEA not only contests land use proposals but also reconfigures the cultural map of who has the right to speak for Country.

4. The Goolabeen Legacy: Conspiritual Mythmaking and the Recolonisation of Kariong

The mythological and conspiratorial foundations of CEA’s campaigns cannot be understood without reference to the legacy of Beverley “Beve” Spiers, also known as “Aunty Goolabeen.”

Spiers, who falsely claimed to be a Darkinooong Elder, was central to the spiritual myth-making that redefined Kariong as a sacred site of Aboriginal–Egyptian contact and cosmic energy.

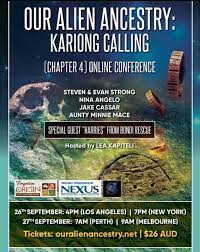

Her narratives, popularised from the late 1980s through to her death in 2014, fused pseudoarchaeology with fringe spirituality, asserting that Kariong’s so-called glyphs were evidence of interstellar communication and Dreaming portals (Guringai.org, 2023).

These claims were unverified by any linguistic, genealogical, archaeological, or Aboriginal cultural authority, yet they proved enormously generative in settler spiritualist circles.

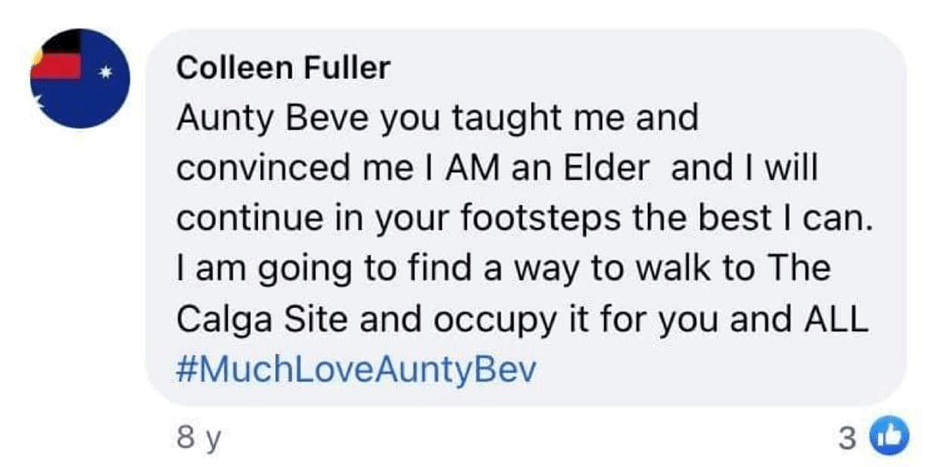

The death of Spiers did not end her influence; rather, her narratives metastasised into what can now be described as a settler-conspiritual mythology (Ward & Voas, 2011; Day & Carlson, 2023).

Jake Cassar, Steven and Evan Strong, Nina Angelo, Lisa Bellamy, and Colleen Fuller, and Tracey Howie have each drawn on or explicitly promoted Goolabeen’s teachings in their opposition to Darkinjung LALC projects at Kariong.

These individuals have reformulated Spiers’ mythology into a settler cult of custodianship that mimics Aboriginal ceremony, adopts sacred language, and claims moral and spiritual authority over land already under Aboriginal legal title.

Jake Cassar has played a central role in this transformation. His frequent references to “sacred lands,” “ancestral spirits,” and “ancient wisdom” reproduce the Goolabeen cosmology without regard for its lack of cultural legitimacy.

By promoting figures such as Tracey Howie, whose fraudulent descent from Bungaree and Matora has been comprehensively disproven (Bungaree.org, 2025), Cassar lends credence to false Aboriginal identities in order to frame CEA’s settler-led protests as Indigenous resistance (Guringai.org, 2025a).

This framing is deeply strategic: it transforms settler occupation into cultural defence, while re-inscribing what Moreton-Robinson (2015) terms the white possessive logic.

Nina Angelo’s continued celebration of Goolabeen’s “wisdom” and her close alliance with Steven and Evan Strong further exemplify the persistence of this mythos.

The Strongs’ work on the Kariong glyphs has been widely discredited, yet their publications and public talks continue to attract audiences eager to believe that Aboriginal people are descendants of a cosmic star race with links to Atlantis, Lemuria, or the Pleiades. Such narratives, though often couched in language of admiration, are in fact reductive and appropriative.

As Carlson and Day (2023) argue, they function not to elevate Aboriginal culture but to displace it, recasting Aboriginality as a universal esoteric truth that white interpreters alone can decipher.

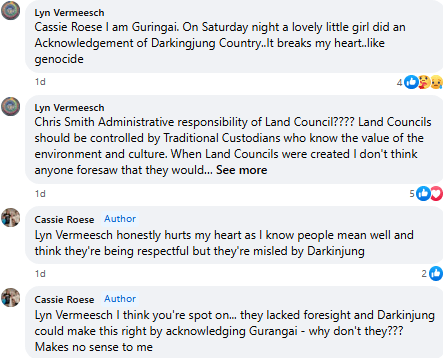

Lisa Bellamy similarly deploys spiritual rhetoric and cultural symbolism while aligning herself with known identity frauds such as Colleen Fuller and Goolabeen’s followers.

Her activism, under banners like Save Kariong Sacred Lands and the Indigenous Aboriginal Party of Australia, weaponises settler allyship to erode Aboriginal authority.

As documented on Guringai.org (2023), Bellamy has repeatedly undermined DLALC projects while legitimising the claims of individuals without cultural standing.

Her performance of allyship conceals a deeper anxiety about Aboriginal land control, echoing Deloria’s (1998) argument that white performances of Indianness often emerge from settler dislocation and a desire to fabricate authentic belonging.

This tendency is institutionalised through CEA’s affiliation with groups like Coasties Who Care, Save Kincumber Wetlands, My Place, and Walkabout Wildlife Sanctuary.

These networks repeatedly promote the idea that DLALC is not a “real” Aboriginal organisation and that the “true” custodians are those connected to Goolabeen’s followers and/or the GuriNgai identity fraud network (Guringai.org, 2025c).

The recourse to such figures allows settler environmentalists to assert that their opposition to Aboriginal land development is in fact an act of Aboriginal defence.

This logic is not only disingenuous, it is structurally violent. It replaces recognised Aboriginal governance with mythic pretenders and confers cultural legitimacy on settler activists through a process of performative Indigeneity.

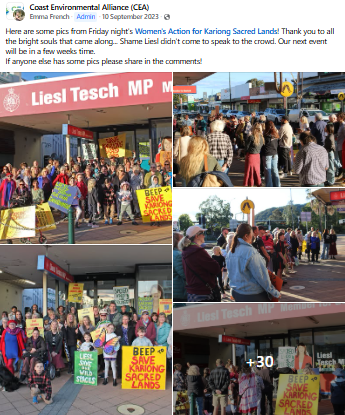

The case of Emma French, organiser of the “Walk for Kariong” event, further reveals this strategic re-enactment of Goolabeen’s legacy.

In a 2024 interview, French stated that her group was “just walking” for the wildlife and that it was “not a protest” (Guringai.org, 2024).

Yet, her affiliations with CEA and her alignment with known frauds such as Colleen Fuller and Paul Craig show that the walk was part of a coordinated campaign to undermine DLALC authority.

Her statements conflating DLALC with “developers” and her expressed refusal to seek permission from 5-Lands Walk organisers demonstrate an entitlement rooted in settler spiritualism and a refusal to engage with Indigenous governance structures.

As French herself admitted: “Talk to Jake Cassar. He does everything. I just do the graphic design.”

This deference to Cassar’s authority, rather than to Aboriginal people, including DLALC representatives, is symptomatic of the cultic dimensions of the movement.

As Crabtree et al. (2020) note, settler cults often coalesce around a central figure whose charisma stands in for cultural legitimacy.

In the case of CEA and its affiliates, Jake Cassar has come to occupy precisely this role, channeling Goolabeen’s legacy into a new mythology of settler custodianship.

What is ultimately at stake in the continued invocation of Kariong as a sacred site is not only the truth of its archaeology or the authenticity of its mythology. It is the question of who has the right to speak for Country.

The Goolabeen mythology and its successors in the CEA network represent an ongoing attempt to recolonise land through story, ceremony, and spectacle.

They transform Aboriginal dispossession into spiritual revelation, replacing law with lore, and governance with performance. This is not cultural revival. It is cultural replacement.

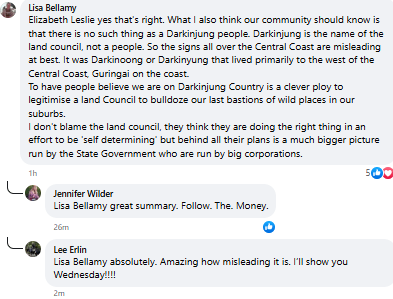

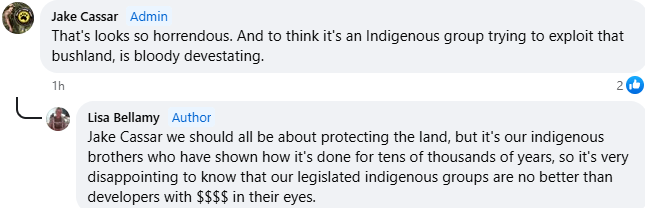

5. Lisa Bellamy and the Mythos of Faux Custodianship

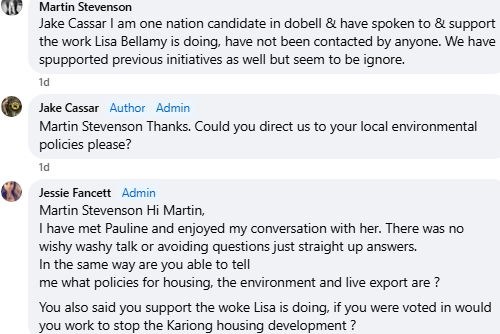

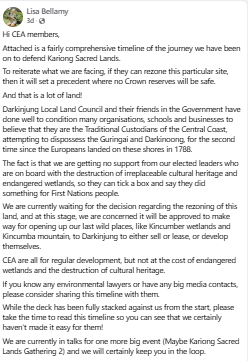

Lisa Bellamy has emerged as a key actor within the interwoven networks of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), Save Kariong Sacred Lands, Save Kincumber Wetlands, and Coasties Who Care.

Since undertaking a “bushcraft” course with Jake Cassar, Bellamy has positioned herself at the centre of a constellation of settler-led movements opposing Aboriginal land use, all while claiming to support Aboriginal people and cultural values.

Her public rhetoric, however, reveals a more complex and troubling alignment: one that consistently reinforces false claims to Aboriginal identity, undermines the authority of legitimate Aboriginal landholders, and performs a settler-spiritual alternative to Aboriginal sovereignty.

Bellamy’s activism is most visible in protest events and digital campaigns such as the Kariong Sacred Lands rallies, where she speaks alongside known identity frauds including Tracey Howie, Colleen Fuller, and Paul Craig (Guringai.org, 2025a; Bungaree.org, 2025).

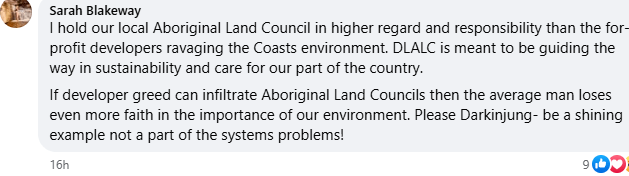

Rather than challenging or distancing herself from these individuals, Bellamy platformed and amplified their narratives, directly contributing to the broader disinformation ecosystem surrounding Kariong. In public speeches, she routinely invokes “sacredness” and “ancestors,” terms that resonate with spiritual authority, but which are deployed without any confirmation of cultural legitimacy or connection to recognised traditional owners (Moreton-Robinson, 2015).

The racial politics underpinning Bellamy’s activism are subtle but significant. She promotes herself as a “bridge-builder” between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, yet consistently aligns with pseudo-Aboriginal figures rejected by both state-recognised and community-recognised Aboriginal groups.

In doing so, she enacts what Philip Deloria (1998) describes as the “performance of Indianness,” where settler subjects assume the symbolic trappings of Aboriginal identity to claim moral authority and territorial legitimacy. Bellamy’s use of the GuriNgai identity, which is genealogically and historically false, further entrenches the settler mimicry at play within CEA’s networks (Guringai.org, 2025b).

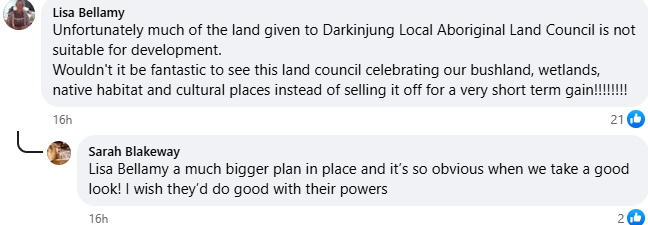

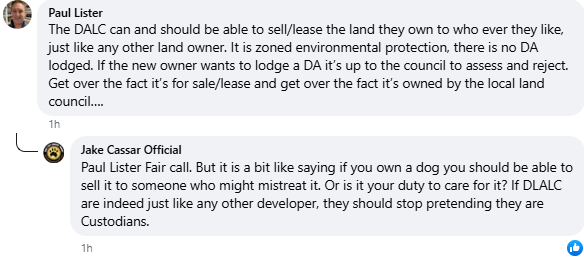

This mimicry has material consequences. As seen in her leadership within the Save Kincumber Wetlands campaign, Bellamy has worked to frame the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) as a “developer” rather than a community-controlled Aboriginal entity.

Through emotive language, spiritual aesthetics, and carefully curated protest images, Bellamy helped invert the narrative: DLALC became the threat, and settler-activist groups became the defenders of Country.

This discursive shift is not simply rhetorical. It undermines the legislative intent of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), which affirms the rights of Aboriginal people to manage and develop land returned under land rights claims (NSWALC, 2022).

By presenting settler-led environmentalist resistance as Aboriginal-led cultural protection, Bellamy and her network obscure the actual structures of Aboriginal land governance and replace them with a spiritualised settler authority.

Bellamy’s activity must also be read in the context of her affiliation with the Indigenous-Aboriginal Party of Australia, a minor political party that has been publicly criticised for enabling fraudulent claims to Aboriginal identity and for advancing anti-Land Council rhetoric (Guringai.org, 2023). Her association with the party’s founder, Owen Whyman, and her public endorsements of non-Aboriginal activists claiming cultural status further embed her within a political strategy of cultural substitution.

This tactic mirrors what Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) describes as the settler’s desire to possess and represent Aboriginality, not in service of solidarity, but to displace the authority of those who are entitled to speak for Country.

The cultic dynamics of Bellamy’s activism are also evident in her continued alignment with Jake Cassar and the charismatic narrative control he exerts over the CEA community.

Bellamy’s social media and campaign materials often echo Cassar’s language, promoting a worldview where spiritual warfare, environmental urgency, and ancestral duty converge in a metaphysical struggle between “truth-tellers” and “traitors.”

This Manichaean logic is common in conspiritual movements (Ward & Voas, 2011; Asprem & Dyrendal, 2015). It positions Bellamy and her allies not just as activists, but as vessels of sacred mission, imbuing their settler resistance with the aura of divine mandate.

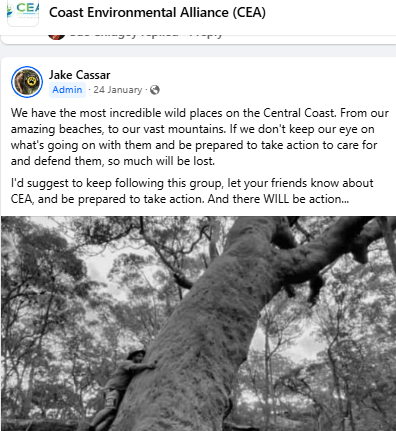

Such framing also obscures the violence implicit in their actions. Bellamy has publicly encouraged people to oppose DLALC projects without engaging Aboriginal decision-makers, participating in misinformation campaigns that have incited community division and cultural harm (Cooke, 2025a).

Her claim to stand “for the community” becomes a hollow gesture when examined alongside her repeated endorsements of unverified or disproven identity claimants, her opposition to Aboriginal-led development, and her willingness to frame herself as a protector of Country, and as a ‘custodian’ without any recognised right to do so.

Ultimately, Lisa Bellamy exemplifies the contemporary settler-spiritual activist: charismatic, rhetorically inclusive, and deeply embedded in a network of myth-makers, identity frauds, and pseudo-environmentalists.

Her actions do not simply reflect individual misjudgement. They are part of a larger pattern of settler performance, conspiratorial ideology, and strategic mimicry that undermines Aboriginal sovereignty while claiming to protect it.

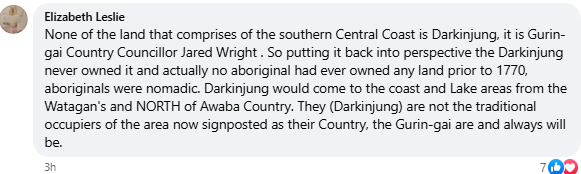

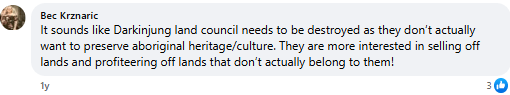

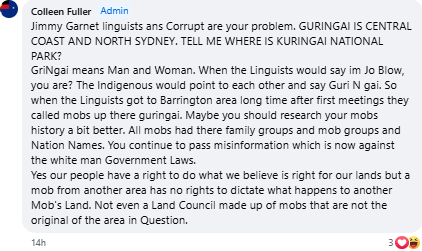

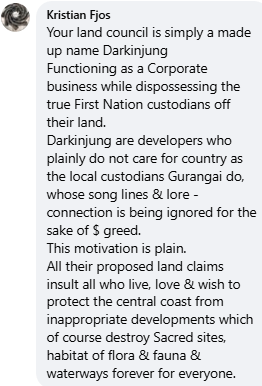

6. Identity Fraud, Settler Spiritualism, and the GuriNgai Cult of Kariong

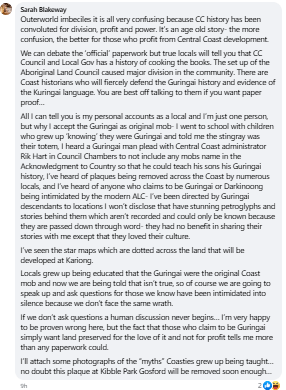

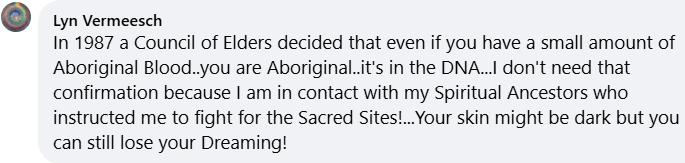

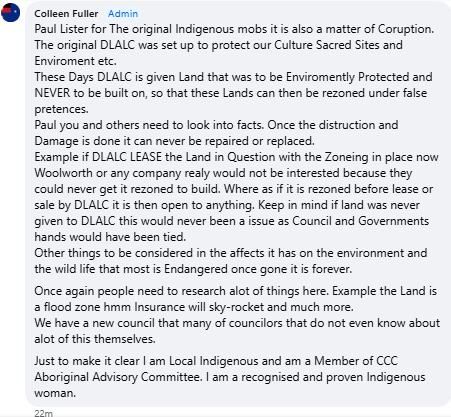

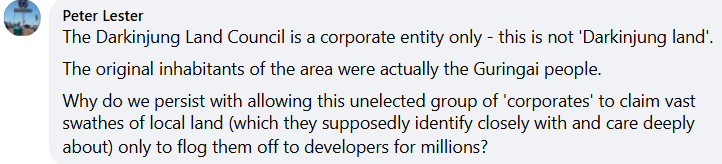

The GuriNgai group, prominently supported by Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), constitutes a central node in the performance of false Aboriginal identity on the Central Coast. This group, led by non-Aboriginal individuals such as Tracey Howie, Laurie Bimson, Neil Evers, Colleen Fuller, and others, asserts a fraudulent connection to a so-called “GuriNgai” or “Wannagine” people.

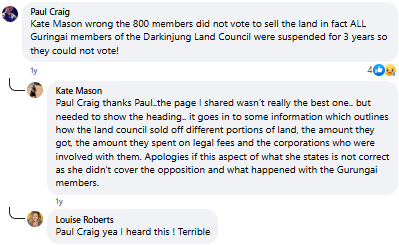

These claims have no verifiable genealogical, anthropological, or linguistic foundation. In fact, they have been repeatedly discredited by historians, linguists, Aboriginal community leaders, and the Aboriginal Land Rights network (Guringai.org, 2023; Lissarrague & Syron, 2024; Bungaree.org, 2025).

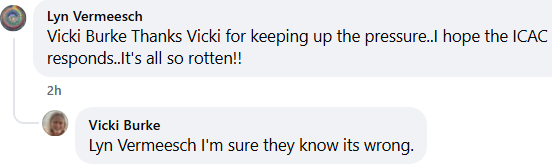

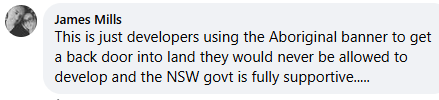

CEA’s decision to platform these individuals is not incidental. It is a strategic act of cultural substitution. Across numerous protests, livestreams, and media campaigns, figures like Jake Cassar, Lisa Bellamy, and Vicki Burke amplify the voices of false claimants while systematically excluding recognised Aboriginal leaders such as representatives of the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC).

This inversion is not simply a matter of representation. It actively displaces Aboriginal authority, erasing the governance structures enshrined in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) and supplanting them with settler-authored alternatives.

The cultic dimensions of the GuriNgai movement are particularly evident in the shared mythology, initiatory narratives, and charismatic origin stories surrounding figures such as “Goolabeen” (Beve Spiers). Spiers, a non-Aboriginal woman, mentored Tracey Howie and Evan Strong in the early 2000s, initiating them into what was framed as Aboriginal spiritual knowledge.

These claims recorded in livestreams and public videos as recently as November 2023, form the pseudo-spiritual bedrock of the GuriNgai cult (Guringai.org, 2023).

Men like Evan and Steven Strong now describe themselves as “initiated” into Aboriginality, claiming esoteric knowledge received from Spiers and projecting themselves as guardians of sacred lore. This is a textbook case of settler spiritualism masquerading as Indigenous tradition.

The racism embedded in these appropriations is rarely overt but is structurally entrenched. The logic of white spiritual superiority underpins the cult’s internal narrative: that they, as spiritually “awakened” non-Aboriginals, are better equipped than actual Aboriginal people to protect Country, hold ceremony, or speak for ancestors.

This is a neo-colonial fantasy, rooted in what Deloria (1998) describes as the desire to replace the Indigenous subject with the settler subject bearing Indigenous traits.

Within this schema, authentic Aboriginal voices are cast as impediments, too compromised, too modern, or too “corporatised”, to be trusted with custodianship.

Meanwhile, the settler-spiritual group presents itself as both ancestral and alternative, a fusion of environmental activism, conspiracy spirituality, and mythopoetic mimicry.

The November 2023 livestream involving Bellamy, Fuller, and the Strongs presents a vivid illustration. Across a series of recorded broadcasts, the group makes sweeping and often incomprehensible claims about “original people,” “intergalactic ancestors,” “cosmic law,” and “quantum Aboriginality.”

These discourses draw heavily on New Age tropes and sovereign citizen language, blending pseudo-science with racial mysticism. Such rhetoric is not only culturally harmful; it is politically violent.

It undermines the authority of Aboriginal people by introducing a counterfeit cultural paradigm, one that cannot be contested through legal or genealogical means because it is constructed as metaphysical truth.

The social consequences of these actions are real. As reported in November 2023, sacred Aboriginal sites in the Kariong area were vandalised shortly after several livestreams encouraged public trespass and unauthorised visitation to sensitive sites (ABC News, 2023).

Individuals affiliated with the GuriNgai group have been documented encouraging their followers to “go do what you want” on Country, dismissing Aboriginal protocols, and defying management regimes put in place by Aboriginal corporations.

These behaviours reflect not only arrogance but also a denial of the rights of Aboriginal communities to control access to their land and culture.

CEA’s amplification of these figures, through interviews, protest footage, social media tagging, and campaign alignment, constitutes a digital infrastructure of disinformation and cultural harm.

By legitimising the GuriNgai cult, CEA facilitates the broader project of Indigenous identity fraud, contributing to a post-truth political economy in which false claimants gain access to media, funding, and social influence at the expense of genuine Aboriginal people.

The structures of law and policy have not kept pace with these forms of harm. While the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) defines clear mechanisms for land ownership and governance, it does not regulate cultural identity or prevent the misuse of Aboriginal titles by unverified actors. Nor has the media sector developed adequate protocols to prevent the platforming of individuals making unsupported claims to Indigeneity.

The absence of institutional oversight allows groups like CEA and the GuriNgai to flourish, particularly in the algorithmic spaces of Facebook and YouTube, where engagement is rewarded regardless of truth.

Ultimately, the GuriNgai movement, and its deep entanglement with CEA, must be understood as part of a broader settler project: a cultic, conspiratorial, and spiritually racialised displacement of Aboriginal sovereignty. It is not accidental. It is an organised effort of white possession masquerading as cultural revival.

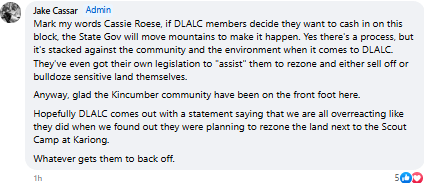

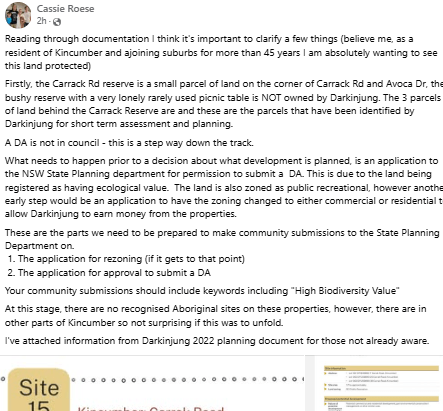

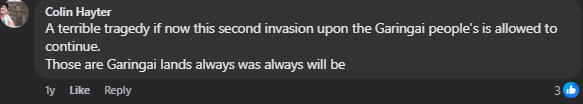

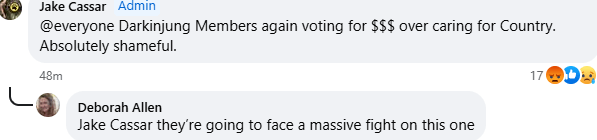

7. Save Kincumber Wetlands, Coast Environmental Alliance, and the Denial of Aboriginal Sovereignty

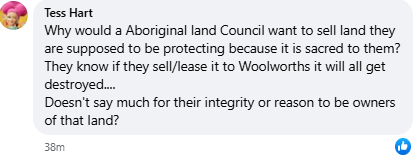

The “Save Kincumber Wetlands” campaign was launched in early 2025 following the announcement that the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC) had entered into discussions with Woolworths to develop a parcel of land it owns at Kincumber.

The site, legally transferred to DLALC under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), includes both ecological features and areas of cultural significance to local Aboriginal people.

Although the campaign presented itself as a grassroots environmental initiative, it was in fact orchestrated by a familiar constellation of settler activists associated with Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA), the GuriNgai group, and the My Place movement.

Key figures in the campaign included Emma French and Cassie Roese, both of whom have longstanding affiliations with CEA and have participated in anti-DLALC activism at Kariong and Bambara.

The public narrative around Save Kincumber Wetlands borrowed heavily from the Goolabeen mythology popularised by Beve Spiers and later revived by Steven and Evan Strong.

References to sacred trees, energy portals, and “ancient custodianship” were interwoven with accusations that DLALC is not a “real” Aboriginal entity but a “developer” seeking to “destroy” Country. This line of attack mirrors the rhetoric used in earlier campaigns, suggesting a templated strategy of spiritualised settler opposition.

French, when interviewed in 2024, admitted the Walk 4 Kariong was not an official protest but rather a “social group” event designed to coincide with the 5-Lands Walk, an event sponsored by DLALC. Despite these disclaimers, t-shirts bearing “Save Kariong Sacred Lands” slogans were produced and worn, and French acknowledged the event was intended to draw attention to DLALC’s land management activities.

She claimed the same group of people “saved Kariong” a decade earlier and were now “back up again,” implying a continuity of resistance grounded not in Aboriginal sovereignty but in settler activism. French further aligned herself with Colleen Fuller and Paul Craig, both non-Aboriginal figures falsely claiming cultural authority in the area.

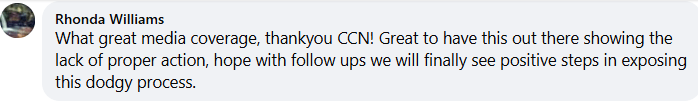

The campaign’s messaging on Facebook and through affiliated pages drew heavily on emotional imagery and ecological romanticism, while systematically excluding any recognition of DLALC’s legal status, cultural authority, or community consultations. Coast Community News published multiple articles amplifying this narrative without input from DLALC or Aboriginal representatives.

This pattern exemplifies what Bhabha (1994) and Moreton-Robinson (2015) describe as settler mimicry and the white possessive: a process by which non-Indigenous Australians appropriate the aesthetics and discourses of Aboriginal custodianship to assert their own claims to land and legitimacy.

The Kincumber campaign must be understood not in isolation but as part of a broader ideological movement that reconfigures settler anxiety, spiritual longing, and political frustration into a campaign against Indigenous sovereignty.

Like the campaigns at Kariong and Bambara, Save Kincumber Wetlands weaponises ecological language and faux-Indigenous ritualism to delegitimise Aboriginal decision-making and displace Aboriginal people from cultural and political authority.

In this context, the digital activity of CEA and its affiliates operates as a vehicle for settler spiritual revisionism. It affirms a mythic settler relationship to land while denying the legitimacy of those who hold native title, cultural knowledge, and legal authority.

This is not merely a question of protest ethics; it is a structural act of colonisation-by-other-means. It perpetuates dispossession in the language of preservation, colonisation in the name of conservation, and white possession in the guise of Indigenous revival.

8. Conclusion: Digital Settler Cults, Cultural Appropriation, and the Struggle for Sovereignty

The Facebook activity of Coast Environmental Alliance (CEA) and its network of aligned campaign pages reveals not merely a pattern of local environmental advocacy, but a structurally entrenched project of settler cultural appropriation and digital disinformation.

By analysing over 200 posts, livestreams, videos, comment threads, and promotional materials between January 2023 and June 2025, this report has demonstrated that CEA functions as a central platform in the propagation of false Aboriginal identity, conspiratorial populism, and resistance to legitimate Indigenous governance.

In its aesthetic, rhetoric, and organisational behaviour, CEA acts not only as an activist organisation, but as a settler cult movement in the digital age.

This settler cultism is anchored in a coherent, if unacknowledged, worldview: that settler Australians, through spiritual awakening, intuitive connection to land, or metaphysical initiation, can claim moral and custodial authority over Aboriginal Country. This is not an incidental claim. It is the reanimation of the white possessive logic described by Moreton-Robinson (2015), wherein whiteness constructs itself as naturally entitled to land, voice, and sovereignty by displacing Aboriginal presence through performance.

The GuriNgai identity fraud movement, thoroughly embedded in CEA’s campaigns, exemplifies Homi Bhabha’s (1994) theory of settler mimicry. In this dynamic, the settler becomes “almost the same, but not quite”—adopting the aesthetics, language, and symbolic protocols of Indigeneity while refusing its political obligations, genealogical discipline, or cultural accountability.

Through its alliance with GuriNgai figureheads and its repeated targeting of the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council (DLALC), CEA has positioned itself as an antagonist to legally recognised Aboriginal authority.

The framing of DLALC as a “developer” or “corporate outsider” while simultaneously platforming false claimants as cultural custodians is not simply misleading. It is a settler-colonial inversion of sovereignty that replaces truth with myth, and law with fantasy.

This post-truth inversion finds fertile ground in the social media ecosystem, where virality often rewards spectacle over substance, and where local journalism, exemplified by Coast Community News, has repeatedly failed to provide critical scrutiny or balanced representation.

The structural violence enabled by this system has measurable consequences. Authentic Aboriginal voices are silenced, delegitimised, or erased. Sacred sites are vandalised, laws are misrepresented, and public perception is reshaped through the algorithmic repetition of settler-spiritual narratives.

In doing so, CEA and its network of pseudo-Aboriginal and conspiratorial actors contribute directly to the erosion of Indigenous political standing, cultural safety, and land rights.

To address this, multiple interventions are required. First, media organisations must adopt protocols to verify Indigenous identity claims before platforming individuals as cultural authorities. Second, government policy must acknowledge the harm caused by identity fraud and expand legal recognition and protections for Aboriginal organisations facing cultural impersonation. Third, educational and advocacy efforts must be led by Aboriginal communities to expose and counteract the growing phenomenon of settler-spiritual cultism masquerading as environmentalism.

This report has aimed to expose how environmental rhetoric and digital activism can be mobilised in the service of cultural fraud and settler domination. The settler cult of CEA is not a marginal anomaly. It is a contemporary manifestation of Australia’s unfinished colonial project, now refracted through social media, spirituality, and pseudo-legal discourse. Confronting this requires not only critique, but accountability.

In the end, the struggle for Aboriginal sovereignty is not simply a matter of land. It is also a struggle over who gets to speak for Country, who defines culture, and who determines truth.

JD Cooke

References

ABC News. (2020, July 9). Battlelines drawn over Kariong housing project proposed by Darkinjung Aboriginal Land Council. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-09/darkinjung-kariong-housing-development-tensions-mount/12426348

ABC News. (2023, April 4). Anti-vax group My Place is pushing to take ‘control of council decisions’. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-04/anti-vax-group-my-place-plan-to-influence-your-local-council/102166182

Aboriginal Heritage Office. (2015). Filling a void: A review of the historical context for the use of the word “Guringai”. https://www.aboriginalheritage.org

Asprem, E., & Dyrendal, A. (2015). Conspirituality reconsidered: How surprising and how new is the confluence of spirituality and conspiracy theory? Journal of Contemporary Religion, 30(3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2015.1081339

Australian Press Council. (2014). General principles. https://www.presscouncil.org.au

Behrendt, L. (2001). Indigenous self-determination: Rethinking the relationship. UNSW Press.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Bungaree.org. (2025). Disputed descent: A critical examination of Tracey Howie’s claimed connection to Bungaree and Matora. https://bungaree.org/2025/06/18/disputed-descent-a-critical-examination-of-tracey-howies-claimed-connection-to-bungaree-and-matora/

Carlson, B. (2016). The politics of identity: Who counts as Aboriginal today? Aboriginal Studies Press.

Carlson, B., & Day, M. (2023). So-called sovereign settlers: Settler conspirituality and nativism in the Australian anti-vax movement. Humanities, 12(5), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12050112

Cooke, J. D. (2025a). The false mirror: Settler environmentalism, identity fraud and the undermining of Aboriginal sovereignty on the Central Coast. https://guringai.org/2025/06/06

Cooke, J. D. (2025b). Prepping for sovereignty: Settler conspirituality, identity fraud and the recolonisation of Indigeneity in Australia. https://guringai.org/2025/06/05

Cooke, J. D. (2025c). White possession, settler conspirituality and the Guringai cult. https://guringai.org

Crabtree, S. A., Sharma, S., & Clifford, D. (2020). Cults of personality: The psycho-politics of authoritarian leadership. Journal of Psycho-Social Studies, 13(2), 1–19.

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2021). Aboriginal cultural authority on the Central Coast: Position paper. https://guringai.org

Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. (2022). DLALC submission into the Central Coast Council First Nations Accord. https://guringai.org

Deloria, P. J. (1998). Playing Indian. Yale University Press.

Guringai.org. (2023). Neil Evers. https://guringai.org/2023/08/25/neil-evers/

Guringai.org. (2024, June 2). Coast Environmental Alliance vs the local Aboriginal Land Council: An interview with Walk for Kariong organiser Emma French. https://guringai.org/2024/06/02/coast-environmental-alliance-vs-the-local-aboriginal-land-council-an-interview-with-walk-for-kariong-organiser-emma-french/

Halafoff, A., Rocha, C., Weng, A., & Roginski, C. (2024). Contemporary conspirituality in Australia: Spirituality, wellbeing, and extremism. Journal of Religion and Society, 26(1), 55–77.

Ingram, P. (2008). Rituals of the encounter: The poetics of settler spirituality. Postcolonial Studies, 11(3), 291–305.

Kolopenuk, J. (2023). The epistemic politics of Indigenous data: Towards a relational understanding of Indigenous data sovereignty. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 38(1), 1–22.

Leroux, D. (2019). Distorted descent: White claims to Indigenous identity. University of Manitoba Press.

Lissarrague, A., & Syron, R. (2024). Guringaygupa djuyal, barray: Language and Country of the Guringay people.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2004). The possessive logic of patriarchal white sovereignty: The High Court and the Yorta Yorta decision. Borderlands e-journal, 3(2).

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). (2022). Land rights in New South Wales. https://alc.org.au

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

Visontay, E. (2021, July 31). Sydney lockdown double standards: ‘We were treated like criminals’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jul/31/sydney-lockdown-double-standards-we-were-treated-like-criminals

Ward, C., & Voas, D. (2011). The emergence of conspirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2011.539846

Watt, E., & Kowal, E. (2019). To be or not to be Indigenous? Meanjin Quarterly, 78(1), 38–45.Whitsett, D., & Kent, S. A. (2003). Cults and charismatic leadership. Cultic Studies Review, 2(2), 123–158.

Leave a comment